Why it’s Hard to Hear and Act on the Feedback We Really Need

By Kat Rippy and Ashley Allen Seeley, Ph.D

We have all worked with great leaders and really poor leaders. The most dubious leaders we have worked with are those with great strengths and amazing potential, but never pushed through to the next level because they got in their own way. This could be the brilliant engineer who has amazing ideas, stretches the boundaries, and takes projects to successful completion, but struggles to delegate, and therefore their plate is always way too full. You may have worked for the CEO who was an excellent people leader, conscious of the business bottom line, and managed multiple business areas successfully, but lacked vision and couldn’t think strategically. Or perhaps you encountered the leader who understood the challenges of the business, elevated others to success, and worked harder than anyone else in the room, but never seemed to make a decision, so everyone was always waiting to move forward. These leaders often leave us wondering if there is anything we can do to help them get out of their own way.

Every one of us faces this same struggle, whether we realize it or not. We all have amazing strengths and contributions only we can make. These are the skills and abilities we should strive to leverage each day. We each also have areas of non-strength, areas to develop, and areas we don’t successfully access. These weaker areas are often the places that create friction with others and can make us difficult to work with.

Even if we are high in Emotional Intelligence, aware of our weaknesses, and try to minimize them, we often don’t know how our weaknesses are experienced by others and the impact they have on our outcomes and results. Did my late data change the project timeline? Does my lack of follow-through demotivate others? How do my evolving priorities ripple to others? These questions are seldom asked and almost never receive accurate and honest feedback when they are.

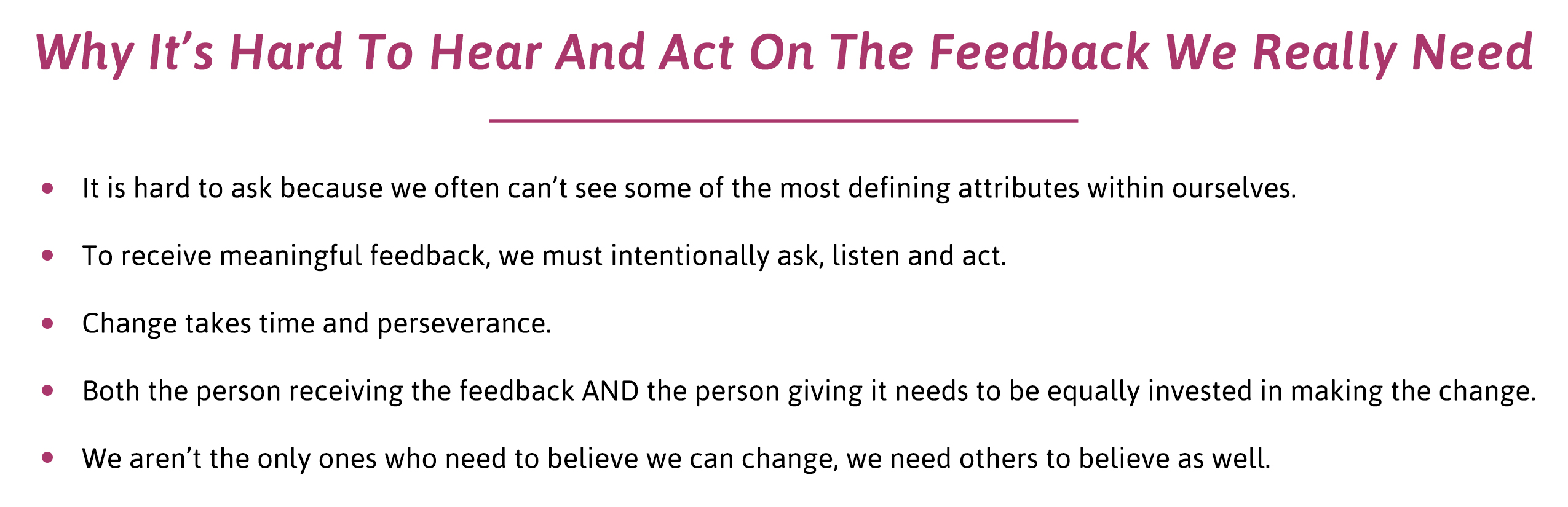

Why is it so difficult to ask for critical feedback that could change our effectiveness exponentially? Why is it even more difficult to give this type of feedback? It is hard to ask because we often can’t see some of the most defining attributes within ourselves. Many of these traits have been part of us for as long as we can remember, some of them may have contributed to our previous success, and most are deeply woven into how we operate every day. Therefore, even when we know feedback is central to growth and development, it doesn’t make it any easier to ask for or digest. Asking for feedback and being truly ready to internalize it and act on it are very different things.

To be truly open to feedback, we need to create an environment with space and intention for feedback. This means feedback is more than an afterthought and takes place outside of formal performance appraisals and mid-cycle reviews. Feedback is not asked for in passing, “How did I do on that presentation?” as you race between meetings. Creating space for feedback is accomplished by slowing down, letting others know what type of feedback you need, sincerely asking, listening with undivided attention, critically processing the information, and taking action when needed. Many of us are so busy with our day-to-day activities that we don’t slow down enough to create this type of space. As a result, people don’t give us real feedback. They give us generalizations or formal documents with little substance. To receive meaningful feedback, we must intentionally ask, listen and act.

When space is purposefully created for feedback, others have an opportunity to give honest and actionable feedback. This type of feedback is specific and valuable. It defines the behaviors observed and clarifies their impact on others, the task, and the organization. Effective feedback opens the door to collaborative conversations that explore solutions and discover new actions that benefit everyone. It feels connective, supportive, and actionable. It facilitates behavior change and helps us become more effective.

The real magic, however, lies in how the feedback is put into action. Upon receiving feedback, we face the choice of whether to utilize it and make changes in our behavior; reject it and make no changes at all; or take a common halfway approach – accepting and appreciating the feedback, making an initial attempt to modify our actions, but ultimately going back to the way things were. Making real change takes a lot of effort. It’s challenging to stretch outside our comfort zone and modify how we do things to better meet the needs of others or the organization. For this reason, we usually either completely reject feedback and justify our behaviors as necessary, or we try to make changes and then give up and go back to our natural ways of behaving.

The real magic, however, lies in how the feedback is put into action. Upon receiving feedback, we face the choice of whether to utilize it and make changes in our behavior; reject it and make no changes at all; or take a common halfway approach – accepting and appreciating the feedback, making an initial attempt to modify our actions, but ultimately going back to the way things were. Making real change takes a lot of effort. It’s challenging to stretch outside our comfort zone and modify how we do things to better meet the needs of others or the organization. For this reason, we usually either completely reject feedback and justify our behaviors as necessary, or we try to make changes and then give up and go back to our natural ways of behaving.

Change takes time and perseverance. The science of neuroplasticity and research on Emotional Intelligence tells us our brain is always organizing itself to focus on its most important goal: keeping us safe. Our brain is happiest when we are doing things in an automated, repeatable way, so it can focus on scanning the environment for threats. When we need to do something difficult or out of our “norm,” our brain has to work extra hard. Perhaps it’s helpful to know that even when we have the best of intentions to finally “be more organized,” “respond more quickly,” or “communicate more frequently,” yet six months later we end up back at square one, it’s partly because our brain wanted that to happen! Therefore, commitment to implementing feedback can’t be fleeting.

One way to stay dedicated to implementing feedback and behavior change and to assist others in applying their feedback is to make feedback and behavior change a two-way street. When we receive feedback and someone asks us to “do something differently,” we rarely think of them as partners in that change. Imagine how it would feel to receive feedback alongside an offer of a helping hand. Someone who’s willing to invest just as much effort into the necessary “change” as we are expected to. Both the person receiving the feedback AND the person giving it needs to be equally invested in making the change.

It’s critical to work through the hard parts, gain the support and reinforcement of others, and garner success as a team effort. Have conversations about what we need from others because they don’t always know what we need from them. When they give us feedback, it’s a perfect opportunity to ask for what will help us most. At times we lack the true belief from those around us that we actually CAN make changes. To gain their support, we need to work diligently to help them see us differently and notice the changes we are making. As we implement the feedback, we should check in often to see if the changes are observed and to reinforce the need to look for new behaviors, rather than relying on old perceptions. More importantly, this garners buy-in so others have the patience to support us through the clunky, messy middle part of the change and don’t lose faith in us. This will support us to not return to our old ways. It turns out, we aren’t the only ones who need to believe we can change, we need others to believe as well. Look for ways to include those around you in your feedback journey and be open to assisting others as they implement your feedback.

Finally, there could be times when we decide not to incorporate feedback. Maybe we completely disagree with the feedback, or we don’t value the person providing us with the feedback. Maybe we simply don’t want to make the necessary adjustments others want us to make. When we don’t incorporate feedback, we are making a choice, whether we realize it or not, that could impact our success and relationships within that environment. When we chose not to hear, see, or take needed feedback, it negatively impacts our ability to be effective and can have long-term consequences on our reputation. Alternatively, this is an important time to check in with ourselves and be honest. If the situation is truly not working for us, we may need to move on. As hard as this option can be, the costs of not doing so may be more harmful than we realize, both for others as well as ourselves.

In closing, when we receive feedback, we need to engage others in our actions and behavior changes. Ask for support and a commitment to seeing it through from all sides. Make it a team effort and everyone will benefit. Establishing new behaviors is the hardest part. Once it becomes the “official” new way of doing things and everyone is invested in it, it’s just as easy as the old way.

Additionally, when we see an opportunity to provide feedback to others, first take the time to consider how we can support them in receiving the feedback and adjusting behaviors or actions. Create opportunities to support others in collaboratively pursuing change and modifying interactions, work approaches, or expectations for everyone to see progress, accept setbacks, and develop a culture of feedback and change.

For more information contact info@energizeleadership.com